June 2018

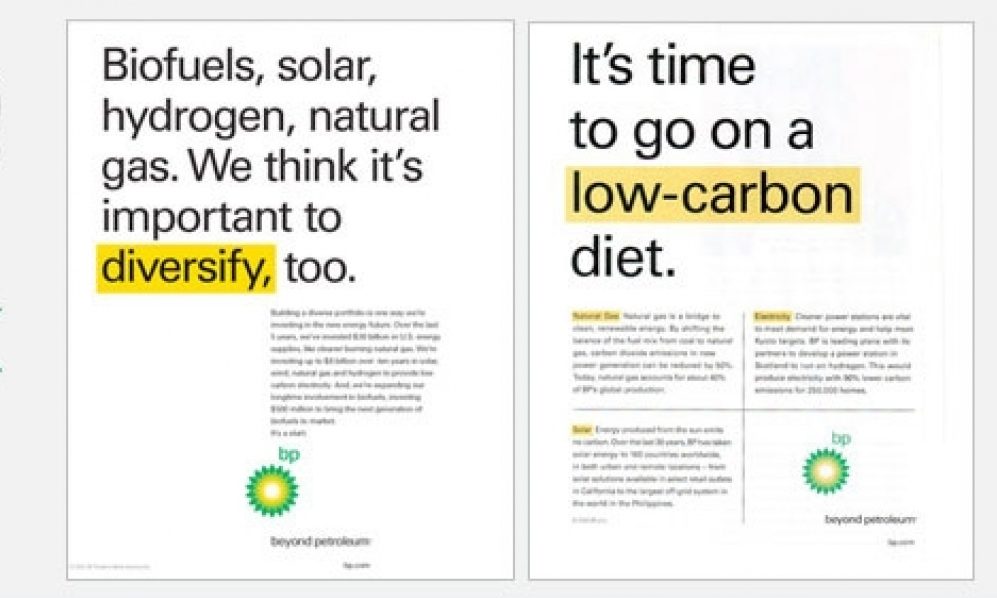

When BP announced, with much fanfare, that it was changing its name to ‘Beyond Petroleum’ and changing its logo to the now-familiar green sunflower in 2000, critics were quick to point out that the company had spent more on the rebrand than it had on renewable energy the previous year.

When BP, in 2005 under its then-CEO John Browne, pledged to spend US$8.3 billion on renewable energy over ten years, this sounded like a significant commitment. But during this period the company had an annual capital expenditure of around $20 billion per year. Even at the peak of its green makeover BP was only committing around 5% of its capital investment to renewables, with the remaining 95% still spent on oil and gas.

Since making these green-sounding but not-very-substantive pledges in the early 2000s, BP has been busily reversing and undermining even these small gestures towards sustainability:

- In 2008, after the departure of John Browne, BP announced it was moving into the highly polluting Canadian tar sands.

- In 2011, in the wake of the Deepwater Horizon disaster, it sold off its solar energy business.

- by 2014, it had ditched much of its wind energy, ended its ten-year renewables investment plan a year early and announced that its only significant ‘alternative’ energy investments would now be in biofuels, which have serious problems of their own.

All of this led leading environmentalist Jonathan Porritt – who had spent years working with BP in the hopes of helping the company transition into a clean energy company – to publicly step away from BP and announce that oil companies are incapable of being reformed. He observed that:

‘The lengths [BP and Shell] went to to justify their continuing investments in new hydrocarbons (to the tune of billions of dollars every year) have become more and more extreme. Even the emergence of the ‘unburnable carbon’ analysis (with the headline that very significant percentages of already proven, extractable reserves of coal, oil and gas will need to stay in the ground to give us any chance at all of avoiding the spectre of runaway – and potentially irreversible – climate change) left them entirely unmoved.’

Then, suddenly, in December 2017 BP announced it was buying a US$200 million stake in the European solar power company Lightsource. The oil giant claimed it was ‘excited to come back to solar’ – but this purchase represents just 1% of BP’s 2017 capital expenditure of US$16 billion, with the remaining 99% going overwhelmingly into oil and gas. The Lightsource purchase could be seen as a cynical move by BP to start obtaining some solar assets now that the industry is becoming more profitable – without making any significant shifts away from its core business in fossil fuels.